Introduction

The recently published Global Terrorism Index (GTI) survey of terrorism around the world in 2022 highlights a number of important trends and developments in the fight against Islamist terrorism in Nigeria. This Deep Dive reviews the key points from the report against historical and regional context, and examines the current situation and possible future developments.

The report indicates that Nigeria has seen an improvement in the number of terrorist attacks and related fatalities, but other sources indicate an expanding footprint, with Islamist terrorist activity spreading from the extreme north-east of the country to more central and southern areas.

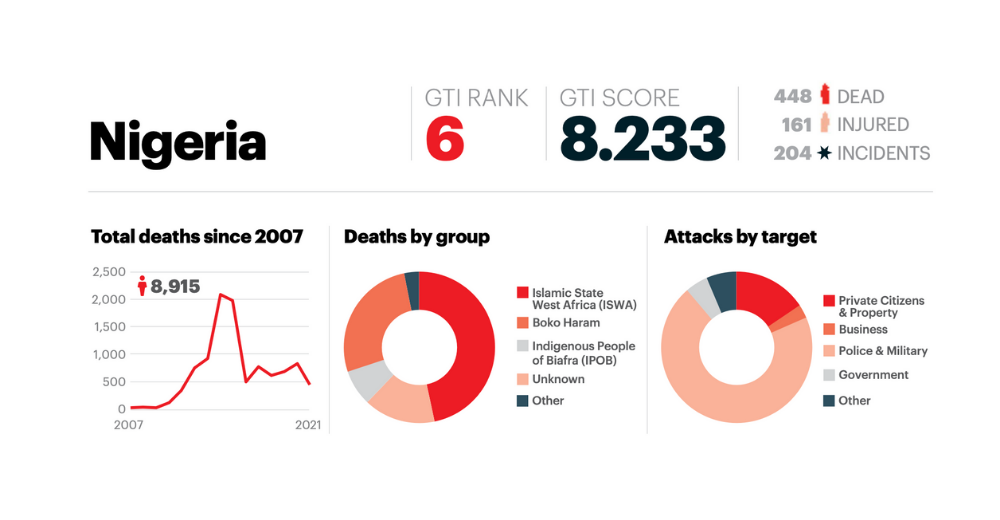

Having suffered at least 865 fatalities in 2020, Nigeria reported a 43% decrease in terrorist deaths in 2021 and a further 35% in 2022. Nevertheless, the terrorist threat posed by Islamist groups Boko Haram (BH) and Islamic State in West Africa (ISWA) remains severe in some areas and significant across the country.

The report indicates that Nigeria lies in eighth position on the table of countries most impacted by terrorism in 2022 – three places lower than in 2021. Burkina Faso and Mali sit in second and third positions on the same table. Complicating this assessment, the Global and International Terrorism Research/Analysis Group in its half yearly report for January-June 2022 assessed that Nigeria was the second most attacked and terrorized country in the world with Iraq being the first and Syria being the third. Their report stated that while Iraq recorded 337 terrorist attacks, Nigeria recorded 305 attacks with Syria coming third following 142 terrorist’s attacks.

This apparent divergence in assessment highlights the problem of using statistical analysis when examining a subject where the definitions of what are relevant or not differ significantly. Some sources quote attacks by herdsmen on farming communities as being terrorist in nature. Other sources attribute the attacks by roving bands of motorcycle mounted bandits in the North West as being terrorism. This problem is also compounded by unreliable reporting of incidents and casualties, with authorities manipulating data to represent a specific operational, social or political agenda point.

Key to note is this analysis does not examine the additional terrorist threats posed by the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) in the south-east region, the issue of marauding bandit gangs in the north-west or itinerant cattle herders in the mid-belt and southern states. Each of these additional elements carry out attacks on communities that are very similar in nature to many of the attacks carried out by Islamist groups however the drivers and motivation behind these attacks are frequently very different, ranging from simple gangsterism to the struggle for grazing rights for cattle herders. Designated as a terrorist group by the Nigerian government in 2017, IPOB has a socio-political agenda and aims to achieve independence from the Federal state, however, IPOB is not a homogenous, singular entity, but more of a franchised brand comprising of numerous factions, each with its own aims and strategy. Additionally although many of the small groups flying the IPOB flag are simply gangsters and extortionists, IPOB elements still accounted for over 40 attacks in 2022 resulting in 57 deaths – its most active and lethal year of operations to date. The threat posed by IPOB will be examined in our next Deep Dive.

Overview

The impact of terrorism in Nigeria continues to decline in terms of both the number of incidents and deaths with the latter falling by 23% from the figures recorded in 2021 and the former falling by 120 attacks as compared with 2021. Overall this represents the lowest attack rate per annum since 2011.

Despite a dramatic reduction in the number of attacks carried out by ISWA (57 attacks resulting in 211 deaths), the group’s lethality increased with 3.7 deaths per attack in 2022 compared to 3.0 in 2021 making it the most lethal terrorist group in the country for the third consecutive year.

Boko Haram (BH) activity also decreased substantially in 2022. Attacks almost halved from 91 attacks in 2021 to 48 in 2022 – the lowest incident rate for more than a decade, but deaths attributable to BH increased slightly from 69 in 2021 to 72 in 2022 – again, and like ISWA, reflecting an increased lethality of their operations.

Terrorist target selection also notably shifted from the police to the Nigerian Army. Nigerian military personnel were targeted in 25 percent of all attacks with civilians the second most targeted group following closely at 24 percent of targeted attacks. The police, previously the preferred target, fell to third place, being targeted in just 18 percent of attacks.

The lethality of attacks increased considerably for civilians, seeing them suffer 196 deaths in 2022, an increase of 78% over the previous year. Conversely, the military, despite becoming the target of choice, suffered 74% fewer deaths in 2022 (58 fatalities) compared to the previous year.

The epicentre of Islamist associated terrorist activity remains the extreme north-east of the country – primarily in Borno State which saw a significant reduction (12%) in terrorism related deaths in 2022. This is largely attributable to the decline of BH, as large numbers of its fighters and supporters surrender to security forces. The erosion of BH combat power is attributable to powerful and well-supported opposition and competition from ISWA, which is now the preeminent terrorist group in Borno State. Severe defeats, mass defections of its members to ISWA, and much improved counter-terrorism efforts by the Nigerian government and foreign military forces generated a perfect storm of challenges for BH, which its dwindling numbers and collapsing support in the indigenous population also significantly undermined its position.

In a reflection of this shift in power between the two groups, in Borno State, ISWA mounted 40 attacks resulting in 168 deaths in 2022. BH mounted just 6 incidents causing 63 deaths. The greater lethality of BH attacks is deceptive as the group is more inclined to carry out mass casualty attacks on soft (civilian) targets than ISWA, which remains focussed on security forces targets. Despite the improving overall trend in the statistics for terrorism, Borno State remains the most kinetic and lethal state in the country. The most lethal terrorist attack of the year occurred in the state when 50 civilians were massacred by gunmen who accused the community of harbouring informants for the security forces.

Contest Between ISWA and BH

The struggle for supremacy between ISWA and BH has its roots in philosophical differences between the Islamic State philosophy and that of BH. ISWA was opposed to mass killings of Muslim civilians, whereas BH used such attacks as a tactic to subdue the indigenous population and force them to support the movement with food, shelter and wives. ISWA was focussed on the broader aims of jihad and the establishment of Islamism throughout West Africa. The two divergent philosophies generated tensions that deteriorated into open conflict between the two factions.

This contest between the two groups is better understood when one examines their origins. Following the 2002 emergence of Boko Haram officially known as Jamā’at Ahl as-Sunnah lid-Da’wah wa’l-Jihād (Group of the People of Sunnah for Dawah and Jihad), the group underwent several evolutions, growing from a small, rag-tag band of proselytising Wahabi idealists armed with spears, bows and arrows and primitive home-made firearms to a well organised insurgent group that uses sophisticated firearms, improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and drones. By 2014, the group had evolved sufficiently to enable it to seize control of most of Borno State and large tracts of neighbouring Adamawa and Yobe as they strived to establish their own caliphate in the Lake Chad Basin. Indeed, in 2014, BH proved to be a more deadly threat than ISIS, reportedly killing as many as 6,664 people. The insurgency spread into neighbouring Cameroon, Chad and Niger Republic, reflecting its essentially Kanuri tribal origins and support base.

The group was responsible for a number of high-profile attacks on communities and security force bases. In 2015, a South African led private military company (PMC), STTEP International, led a successful surge operation that drove BH and ISWA elements out of many areas, pushing them back towards Lake Chad. This setback, saw BH on the defensive, coming under attack by an increasingly well trained (mainly by foreign military training teams) Nigerian Army. In 2016, Islamic State in the Levant (ISIL) announced that it had appointed Abu-Musab al-Barnawi as the new leader of the group. The existing BH leader at that time, Abubakar Shekau, refused to accept the new leader, creating division within the group between those that supported Barnawi and those loyal to Shekau. Those loyal to Barnawi adopted the name of Province (ISWAP), later changing to Islamic State in West Africa (ISWA). This development introduced significant increased complexity into the security environment in Nigeria.

Following the factionalisation of BH, attacks by Shekau loyalists on communities, farmers and schools escalated, triggering an internationally supported effort to mount a counter-insurgency campaign by Nigerian security forces. Nevertheless, the attacks continue. Estimates indicate that by March 2022 the insurgency had resulted in the deaths of at least 350,000 people and 3 million had become internally displaced persons (IDPs). Despite the hard-core members of BH continuing the insurgency, large numbers of less committed fighters have surrendered to security forces. Between July 2021 and May 2022, a total of 13,360 BH fighters and 13,468 BH family members surrendered to security forces. This flow of surrendering BH fighters has continued into 2023 and continues to weaken the group. Even in the face of a steady erosion of its combat power, BH remains a potent threat and is capable of mounting complex and ‘spectacular’ attacks at times and places of its choosing.

On 24 January 2023, more than 200 Boko Haram fighters surrendered to security forces at military barracks in Konduga and Banki in Borno state following an attack on the group by the Islamic State in the West African Province (ISWAP). ISWAP attacked BH camps in Mantari and Maimusari in Bama, also in Borno State. The attack continued a sequence of attack and counterattack by the two groups on one another’s positions that began in early 2020. The clashes have claimed at least 1,320 lives from both groups in a prolonged battle for supremacy.

Terrorists Embrace New Technology

In the period preceding the conflict between BH and ISWA, the latter embraced their fellow Islamists to the extent that BH fighters were being trained at terrorist training camps in the Sahel and Middle East. This allowed the group to exploit the use of IEDs and more advanced tactics techniques and procedures. Their attacks became more lethal and effective in overrunning and defeating the Nigeria security forces. While the IEDs being used by BH were relatively primitive compared to the very advanced technology seen in Iraq and Syria, their introduction changed the way the campaign was being fought. Security forces suddenly found the roads to be a much more dangerous proposition as several vehicles were destroyed by IEDS and lives were lost. Additionally, the introduction of person-borne, suicide IEDs introduced a major new threat to security check points, as well as civilian targets such as markets and places of worship.

Boko Haram also introduced drone technology into its arsenal of weapons and operating systems. Using drones for both reconnaissance purposes and also to deliver explosives to security forces targets was yet another gamechanger. According to the GTI report, 65 non-state actors are now assessed to be capable of employing drones as weapon systems. The technology can be purchased easily in open markets. Modern drones have long-ranges – up to 1,500 kilometres – and can be used in swarm attacks where the sheer number of drones ensures that some will evade security forces defences. They can also be used in targeted assassinations. Operators can be trained easily and quickly. While effective countermeasures to drone technology do exist, it is believed that the Nigerian security forces are yet to introduce such systems, although there are moves to identify a suitable system for deployment in high-risk areas.

An Expanding Operational Footprint

According to a separate analysis based on data from sources close to the Nigerian security forces, in 2022, ISWA claimed responsibility for 25 percent of Islamic State attacks worldwide. The group mounted 517 attacks in Nigeria and a further 30 in the Lake Chad region. The death toll from these attacks amounted to 1,589 deaths.

Within Nigeria, the group has claimed least 25 attacks beyond the North East geopolitical region, supporting the assessment that the group has developed and positioned several well organised and resilient cells beyond its North East / Lake Chad Basin main footprint.

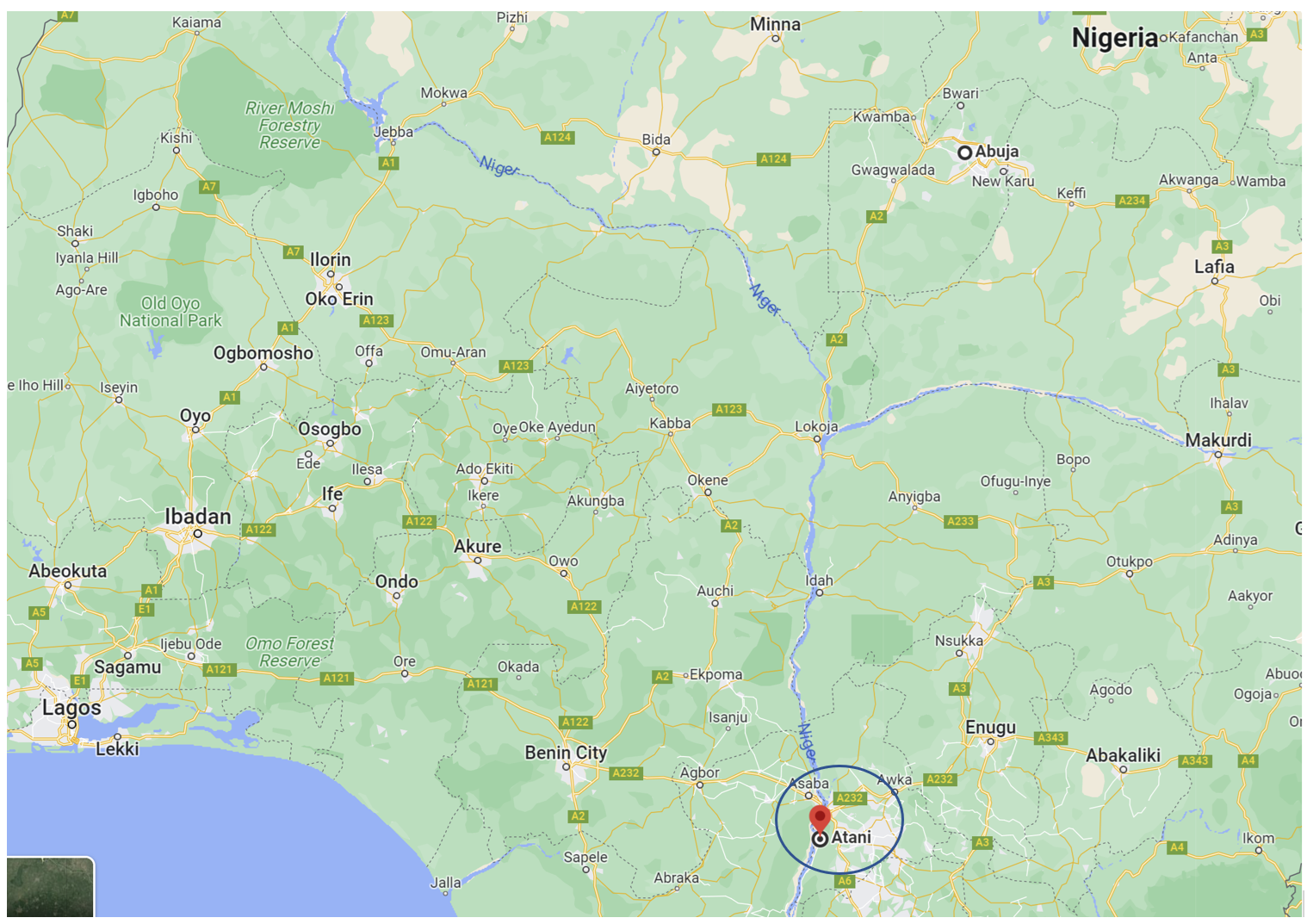

Attacks were mounted in 8 states in 4 geopolitical zones (North West, South-South, North Centre and the South West). The majority of attacks took place in the Middle Belt, with a main effort in Kogi State and single attacks in Taraba, Niger and the FCT. The main area of operations is in the centre of Kogi State. The tempo and variety of attacks indicates that a well-trained and well-resourced cell exists in or close to Lokoja.

The Kogi cell mounted 13 attacks over a 12-month period. Within Kogi State, attacks occurred in Adavi, Okene, Okehi, Ajaokuta, Kabbah Bunu and Lokoja Local Government Areas (LGA). Most took place within 40 kilometres of Okene Town in the Okene LGA. Two attacks were mounted further afield in the vicinity of Owo Town, Owo LGA, approximately 85km away. The cell also carried out attacks in Edo and Ondo States.

Attacks in Taraba were concentrated around Jalingo, indicating the presence of an active terrorist cell in or in the environs of the city. The Taraba cell is likely smaller and less resilient than the Kogi cell. A series of arrests in June 2022 disrupted its operations. However, the contiguous borders with the north-eastern states and the survival of some members of the cell mean that it has the potential to be reconstituted and reactivated rapidly and easily.

In both areas, a small majority (56%) of attacks targeted civilians, with bars in both Taraba and Kogi State being the most frequently targeted. Security forces – primarily police vehicle patrols, checkpoints and police stations – were also targeted. Additionally, 3 large scale attacks were mounted against high profile targets – a train, a prison and a military holding facility. Overall, attacks comprised of 2 instances of kidnap for ransom (each with multiple victims), 15 complex attacks with small arms and IEDs, 8 attacks mounted using just IEDS, 1 assassination and 2 prison breaks. The attacks resulted in 100 deaths, 51 injuries and 177 people being abducted.

Civilian target locations were apparently selected because they would allow the inflicting of mass casualties and were mostly frequented by people whose characteristics and behaviours made them more likely to be targeted by fundamentalists – e.g. Christians and alcohol drinkers. No individual tribal or ethnic group was specifically targeted, but the purpose of the attacks was probably to inflict mass casualties to frighten and intimidate the civilian population and influence the behaviour and decisions of other audiences including federal and local government, local community and political thought leaders and finally, other Islamist groups.

During the attacks and their aftermath, the attackers exhibited very little selectivity in the way the treated their victims. In the case of the Abuja-Kaduna train attack, middle class Nigerians were targeted irrespective of tribe or religion. Muslims were killed, abducted, abused and ransomed alongside Christians.

In all instances, the attackers killed without restraint. IEDs were also used as part of complex attacks against the Wawa Cantonment, Owo, Kuje, Kaduna-Abuja Train and other targets. Nevertheless, most casualties were caused by small arms fire. Apart from the large-scale attacks such as at Wawa and Kuje, the cells employed weapons that can be easily obtained, hidden, moved, or even manufactured.

ISWA has demonstrated a sophisticated use of the information space in its campaign, with information exploitation being a key component of its operational cycle. They rapidly disseminate detailed claims covering the location and number of casualties of their attacks. These statements are accompanied by high-quality imagery. It is assessed that ISWA reports their attacks immediately in order to dominate the information space, confirm their actions and achieve greater influence over their target audiences. It is probable that the cells exploit local languages using multiple mediums and channels.

Regional Context

As ISWA surges to pre-eminence in Nigeria and beyond, the spatial dynamics of terrorism in the region have shifted. The primary area of terrorist activity in the Sahel region currently lies in the tri-border area of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger (also known as Liptako-Gourma). Whilst this region does not feature in western news media as prominently as Syria and Iraq did during the height of ISIS activity, the Sahel is currently the region of the world most affected by terrorism. In contrast to Nigeria and Niger, which have seen falling rates of terrorist activity in 2022, the tri-border region has seen a dramatic deterioration in security. Burkina Faso and Mali occupy the second and third slots in the GTI report table of countries most impacted by terrorism. The two countries saw terrorism deaths increasing by 50% and 56% to 1,135 and 944 deaths respectively. Additionally, four of the ten countries in the Sahel feature in the ten worst scores in the GTI report.

Benin and Togo are also impacted, with both recording more than ten deaths for the first time. Furthermore, reporting also indicates the spread of Islamist extremism into northern Ghana and Ivory Coast.

With regards to BH while their eminence peaked in 2014, i.e., when the group controlled huge swathes of territory in north-east Nigeria as well as areas in neighbouring countries around the Lake Chad Basin, its conflict with ISWA has seen many of its fighters displaced into neighbouring countries. While this has seen its power and influence severely eroded in Nigeria, the group remains relatively stable in other areas of the Lake Chad Basin. In neighbouring Niger, deaths in the Diffa region rose by 38% to their highest level in two years and it is believed this rise has been driven by the displacement of BH elements from Borno State due to pressure from ISWA attacks. The displacement of BH fighters elevated the group’s position in Niger, making it the country’s most deadly terrorist group in 2022.

Conclusions

Although BH continues to atrophy within Nigeria, ISWA remains a potent threat and has shown an intent to expand its operations both geographically and in terms of its targeting.

The conflict between the two groups continued throughout 2022 and is likely to persist throughout 2023. The trajectory of this conflict indicates that BH will be reduced to a mere shadow of its former strength in Nigeria and ISWA will continue to be the dominant Islamist group in the country. Given the wider, regional connectivity that ISWA enjoys, it will likely prove an even tougher opponent for the Nigerian Security Forces than BH has been historically.

The outcome of the 2023 Presidential and Senate elections in the country are yet to be settled, with robust lawsuits filed against the President Elect and INEC. Whether or not the President Elect is inaugurated in May, the security environment in Nigeria will remain complex, dynamic and extremely unstable for the foreseeable future.