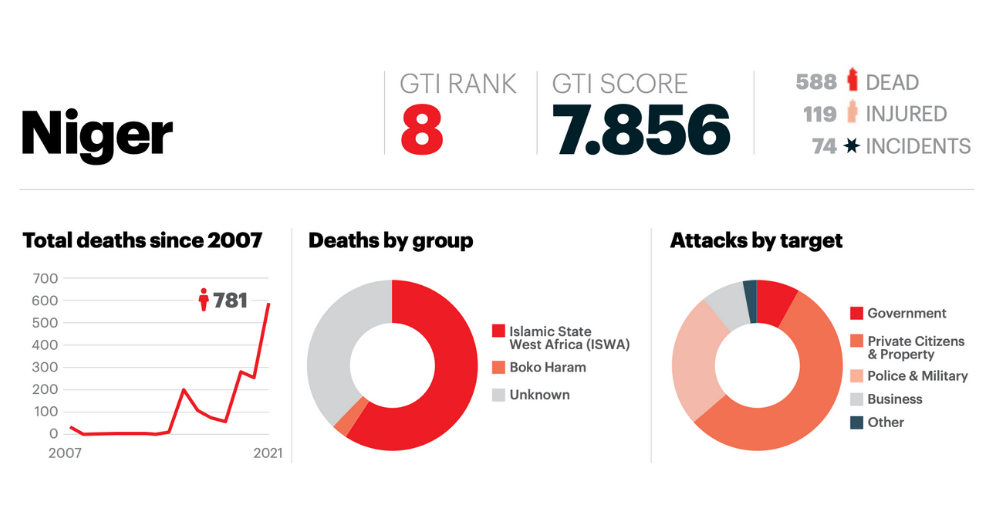

Background

With the world’s eyes looking towards the stand-off between Russia and Ukraine / NATO, we discuss whether the potential instability to the energy supply will trigger an increased interest by the EU in securing the sea lanes and the supply of LNG from West African suppliers.

The potential for armed conflict in Europe remains significant at this time and any outbreak of hostilities will likely lead to an immediate interruption of existing natural gas supplies to Western Europe.

Not only would this have a profound economic impact in those markets, but also on the Russian economy, which is already suffering under the pressure of sanctions imposed following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and their continued support for ethnic Russian separatists in Eastern Ukraine.

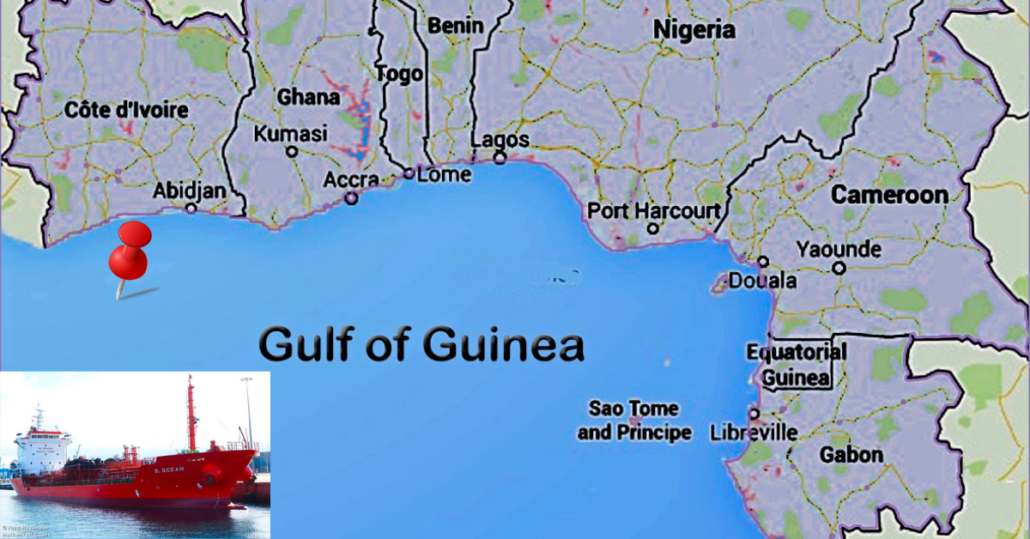

In event of (continued) disruption, Western consumer countries may well seek to acquire LNG supplies from other world producers, e.g. those in the Gulf of Guinea, resulting in a potential consolidation of recent western interest in securing the Gulf of Guinea maritime space and sea-lanes from piracy.

At present tensions between Russia and Ukraine are contributing to the soaring price of oil, which has risen almost 60% in 12 months from around $60/barrel in February 2021 to $94.42 on 11 February 2022, noting that the general rise in oil and gas prices also has been partially triggered by economies recovering from the effects of lockdowns imposed in order to battle the Covid-19 pandemic. (Click here to read more)

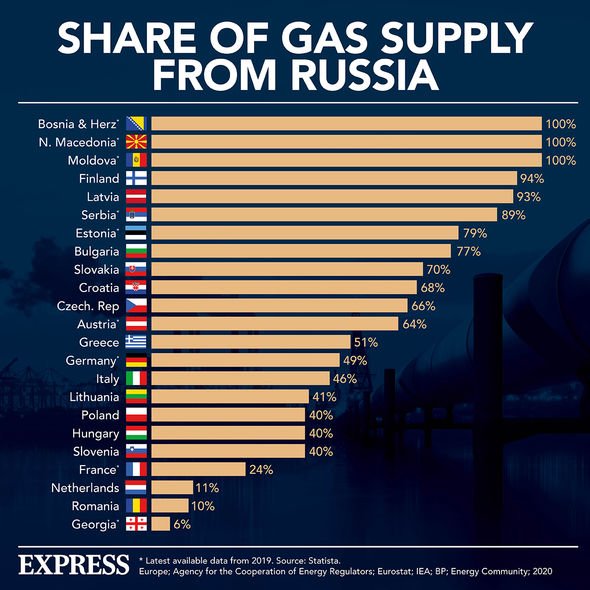

Europe’s Gas Suppliers – How Important is Russia?

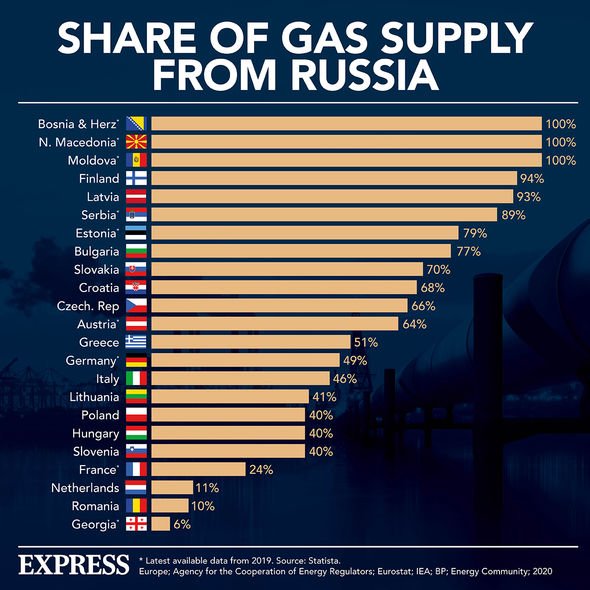

Russia has built itself a position as the major supplier of gas to much of Europe (by example it is the sole supplier to some Balkans countries and supplies more than 50% of the gas consumed in most of the rest of the Balkans and the Baltic States). The UK, by contrast, imports very little Russian gas. However, Russian gas is, without doubt, a strategically important source of energy in most of Western Europe, as the graphic below clearly illustrates.

(Image source – Click here)

Overall, more than 30% of Europe’s gas supply comes from Russia and several strategically vital pipelines run through Ukraine. Even if Russia decides not to ‘weaponise’ the supply of gas, the pipelines would almost certainly be disrupted by any fighting in Ukraine. Russia has used the supply of gas as a political weapon in the past, e.g. when it turned off the supply to the Georgian Republic in 2006 as part of a political strategy to force the Georgians to abandon plans to join NATO. (Click here to read more.)

Nevertheless, it is unlikely that Russia would cut gas supplies to Europe completely – at least not intentionally – as this would be as damaging for the Russian economy as for those it supplies. In addition, Moscow is currently working very hard to get the Nordstream 2 pipeline commissioned to bring gas to western Europe via the Baltic route (achieving this would dramatically reduce the EU’s reliance on the gas coming through Ukraine and potentially allow Moscow to achieve its geostrategic aims regarding Ukraine with much less interest coming from Brussels).

However, limited reductions could apply enough pressure to drive a political accommodation of Putin’s demands. The principal targets would likely be Germany and France – seen as the two biggest influencers in the EU and important member nations of NATO.

While the EU has threatened to impose damaging sanctions on Russia if it invades Ukraine, the position of the 27 states is not homogenous and the issue has created and exposed divisions with the bloc. The EU’s fragile position has gained the attention of Washington and might have been a significant factor behind President Biden’s call for other world producers to ramp up their production. (Read more by clicking here)

Can Africa fill the Gap?

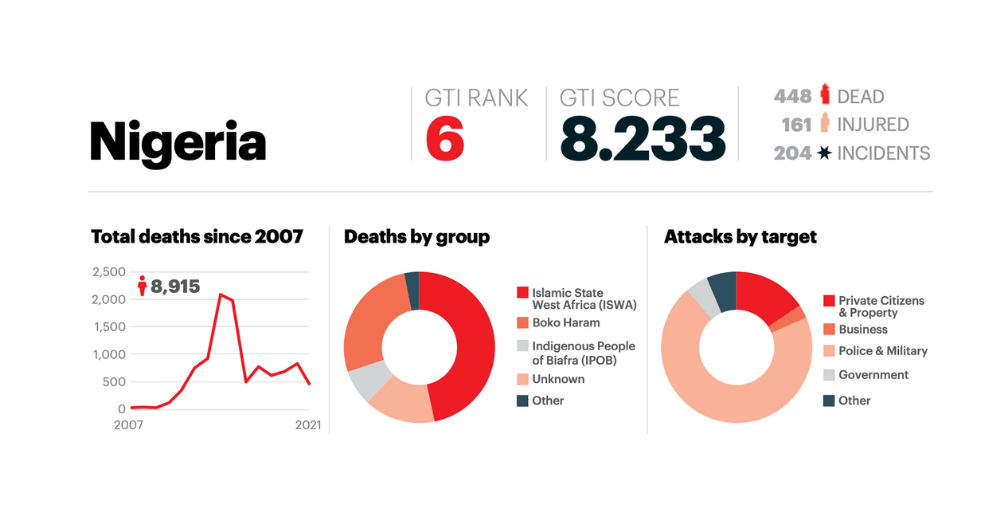

Africa has a number of producers of LNG, including Nigeria, Angola, Egypt, and Algeria. The two biggest African producers, Algeria and Egypt, are Mediterranean countries with relatively short supply chains into the European markets. However, only Algeria has the ability to export gas to Europe via a pipeline – the Maghreb–Europe Gas Pipeline which runs via Morocco to Spain (Click here to read more)– and Egypt’s LNG plants are already operating at capacity. (Click here to read more)

Despite the advantages of short supply chains and existing infrastructure in the two Mediterranean producers, Nigeria reportedly exported more LNG than any other African country in 2021 (in 2020, Nigeria was also the world’s 6th largest producer and exporter of LNG). Click here to read more.

Nigeria Liquefied Natural Gas (NLNG) has also started the long-awaited Train 7 project at Bonny, which will increase the country’s production capacity from 22 to 30 million tonnes per annum. Most of this increased production will be exported to foreign markets. This existing and future supply of LNG from Africa’s top producer is not only vitally important for the country’s economy, but it could also help diversify global supply and fill the gap if Russian gas supplies are interrupted.

But supplies from Nigeria are not without problems. NLNG’s bonny terminal has been forced to declare force majeure in the past due to interruptions of the supply of feedstock to the plant. These have been caused by technical failures on pipelines as well as security-related interruptions of the flow of gas. The challenges in the supply chain do not end at the liquefaction plant. The plant itself has been the site of security incidents and the LNG carrier vessels have also been targeted – although perhaps not as frequently as other types of tanker.

So the key question perhaps is, can Nigeria be regarded as a reliable supplier to European markets given the problem of piracy in both Nigeria and elsewhere throughout the Gulf of Guinea.

Historical Targeting of LNG carriers?

LNG carriers are targeted less frequently by pirates than other classes of vessels in the Gulf of Guinea. This might be a reflection of their lower numbers in the region and the lower rate of them presenting themselves as a target, but as can be seen from the incident summaries below, they are often fired upon by pirate groups (despite the inherent risks involved in attacking such vessels).

Arete has records of at least 14 attacks on LNG carriers in the region since 2014 and in almost every case, the attackers failed to board the vessel and it was able to continue to sail to its destination. Despite these statistics, the threat to vessels of this class remains high, with opportunist attacks on vessels close inshore and more organised pirate operations in the deepwater environment – possible for crew kidnap. Indeed, the pirates are becoming more sophisticated in their planning and

execution of their attacks and they are apparently using their own intelligence-gathering capabilities very effectively in the selection and targeting of specific vessels.

24 April 2014. An unidentified LNG carrier was approached by a suspicious vessel as she was underway 40 nm south of Brass. The master raised the alarm, increased speed, altered course, activated fire hoses, and had the crew direct searchlights toward the small boat. After 10 minutes the small boat departed the area.

05 February 2016. The Liberian flagged LNG carrier Pskov, IMO number 9630028, was attacked approximately 16nM SW of Bonny Island while steaming. Seven persons wearing dark boiler suits with red caps in a speed boat chased and attempted to board the tanker underway. The alarm was raised, fire hoses activated, Master increased speed to maximum and took evasive manoeuvres. When the speed boat was close to a distance of 10 meters, machine guns and a ladder were sighted. Due to the hardening measures taken by the Master, the persons aborted the attempted boarding and fled.

20 April 2016. The Spanish-flagged LNG Tanker TMO Knutsen Bilbao, IMO number 9236432, was attacked 13nm SW of the Bonny Fairway Buoy and 22nm South-South-West of Bonny. The tanker turned around. The vessel escaped the attack and proceeded to the LNG terminal at Bonny.

10 March 2017. While proceeding to Bonny, the Spanish flagged LNG tanker, MT La Mancha Knutsen, IMO number 9721724, was attacked by 6-7 men in a speedboat 9nm from Akpo field. After taking evasive manoeuvres and an increase in speed, the vessel was able to evade the attackers. The pirates were unable to board and all crew were reported safe. After the attack, a ladder was observed on the tanker and the speed boat was observed heading east (In between Bioko Island & Sao Tome).

29 April 2017, the Bermuda flagged LNG carrier, LNG Lokoja, IMO number 9629960, was attacked approximately 40 N miles South West of Bonny terminal. The attack occurred after the escort vessel departed and when NNS military vessel was supporting the Vectis Progress in the same area. Two inflatable RIBs with 4 or 5 armed men on board approached the LNG tanker and fired 5 to 10 shots at the accommodation area of the vessel. The vessel implemented BMP4 measures, increased speed, altered course and took defensive action (VHF16 alarm, use of water spray, barbed wire). The vessel managed to escape. After short pursuit, the assailants abandoned their pursuit.

21 October 2017, an unnamed LNG tanker, possibly Bermuda flagged LNG Bonny II, IMO number 9692002, was attacked approximately 5 nm south of the Bonny Fairway Buoy. According to one source, the pirates attempted to board the tanker.

06 November 2018. the Bermuda-flagged LNG tanker LNG River Niger, IMO number 9262235, was approached and pursued by a single speedboat with 9 armed men on board 30nM SSW of Bonny. The vessel was underway at 17.2kts at the time of the approach and was inbound to Bonny having transited from Altamira (Mexico). The pirates fired upon both the starboard and port sides. Master enacted evasive manoeuvres and crew retreated to the citadel. Two bullet strikes on the bridge below the centre window. Attack failed and the Nigerian Navy escorted the vessel to Bonny.

March 2019, the Bermuda flagged LNG tanker, LNG Akwa Ibom, IMO number 9252209, was approached by 2x boats with 6x men in each boat all dressed in black with red ribbons, approximately 66nm SW of Bonny Fairway Buoy, whilst inbound to Bonny NLNG Terminal. One speed boat crossed the vessel bow but an armed escort vessel responded and as she approached the 2x speed boats left the area.

28 December 2019. the Bermuda flagged LNG tanker, LNG Lokoja, IMO number 9269960 was attacked approximately 195NM WNW of Libreville, Gabon and 70 nm NW of Sao Tome while en route to Bonny. Attack was launched from a single speedboat with 10 armed men on board. The pirates opened fire on the vessel. The vessel conducted evasive manoeuvres. The tanker later was approached by Nigerian patrol boat Defender 6, and as of 1430 hrs, local time was underway heading for Bonny, escorted by Defender 6 and the Portuguese Naval vessel Zaire.

17 October 2020. the Marshall Islands flagged LNG tanker MT Methane Princess, IMO number 9253715, was boarded whilst at anchor in position 03:46.57.443N 008:41.52.62E, off Malabo in the Punta Europa Anchorage. The vessel was attacked shortly after breaking offloading operations. The alarm was sounded and all on deck were able to retreat to the citadel. 2 Filipino nationals were on the jetty and both were taken hostage. One of the hostages jumped off of the pirate vessel and was rescued but sustained injuries. One person entering the citadel was also injured. Total of 1 hostage taken.

05 December 2020, the French-flagged LNG tanker, MT Verrazane, IMO number 9649146, was approached approximately 210nm South of Lagos. The alarm was raised, and the accompanying security escort vessel (SEV) was vectored towards the approaching speedboat. The perpetrators abandoned the approach on spotting the SEV.

18 December 2020. The Bermuda flagged LNG tanker LNG Lagos II was approached while in transit by one-speed boat containing 8-10 175nm SW Bayelsa State. Alert raised onboard. The vessel started evasive manoeuvres. One ladder was spotted on board the speed boat. Speed boat stopped the approach. Vessel and crew are safe.

08 February 2021, the Spanish flagged LNG carrier, LMNG Madrid Spirit, IMO number 9259276, noticed a skiff approaching at high speed while underway approximately 50nm SW of Sao Tome Island. Alarm raised, crew mustered and SSAS activated. As the skiff closed in, hooks and a ladder were noticed, and the pirates fired upon the tanker causing damage to the accommodation. Master increased speed and commenced evasive manoeuvres, resulting in the skiff aborting the attack and moving away. Crew and ship safe.

So Will Instability in Europe Lead to An Increase in International Naval Presence in the Gulf of Guinea?

At present we have seen a number of western naval units deployed into the Gulf of Guinea. Units of the Italian, Danish and British (even Russian) navies have all operated in close cooperation with the Nigerian Navy and other indigenous regional navies and have actively prevented acts of piracy on the high seas. Multinational exercises also bring foreign vessels into the region and foreign vessels pass through on visits and liaison missions, however, there is still little momentum behind the creation of a standing naval force for the Gulf of Guinea among extra-regional powers. This may be driven by local political drivers and a feeling among indigenous navies that allowing a permanent international naval presence might be seen as an abrogation of their duties and an admission of failure in dealing with the piracy issue.

It must also be remembered that instability in Europe would most likely be brought about by a conflict which in turn would likely result in most European naval assets being held back in home waters to generate presence and a capability to respond to potential aggression or escalation of any conflict.

Given this, any deployment of assets to secure the Gulf of Guinea would likely be limited to smaller vessels such as the Offshore Patrol Vessels, i.e. vessels like HMS Trent which recently deployed to the region from the UK. However, without any basing rights and/or an established partnering relationship with at least one indigenous navy, even deployment of OPV might require a fleet logistics vessel to operate in support. This might be achievable if the force were a multinational force, but it would still take a valuable asset away from much higher priority tasks in European waters.

In the absence of a western naval presence, it is possible that we might witness non-NATO nations filling the void, possibly with the Chinese paying greater attention to the region. It is already rumoured that China has reached an agreement with at least one Gulf of Guinea nation to allow the basing of Chinese vessels in the region. The unanswered question is, how will Chinese – or any other foreign naval units – operate in the region? Will they be working as an autonomous force-based locally, or will they work in partnership with and under command of indigenous navies?

In the short term, we will likely see very little foreign activity in the region as all the key maritime nations address problems closer to home. However, in the event that Europe needs to replace lost Russian gas supplies, we could easily see a greater effort by EU countries to address the security challenges faced by commercial shipping off the West African coast. We have seen such a response in the past when the shipping lanes through the Gulf of Aden and off the Horn of Africa became so heavily plagued by piracy that it impacted western economic interests. The same might apply in the Gulf of Guinea in the event of any long term loss of equilibrium in Europe.

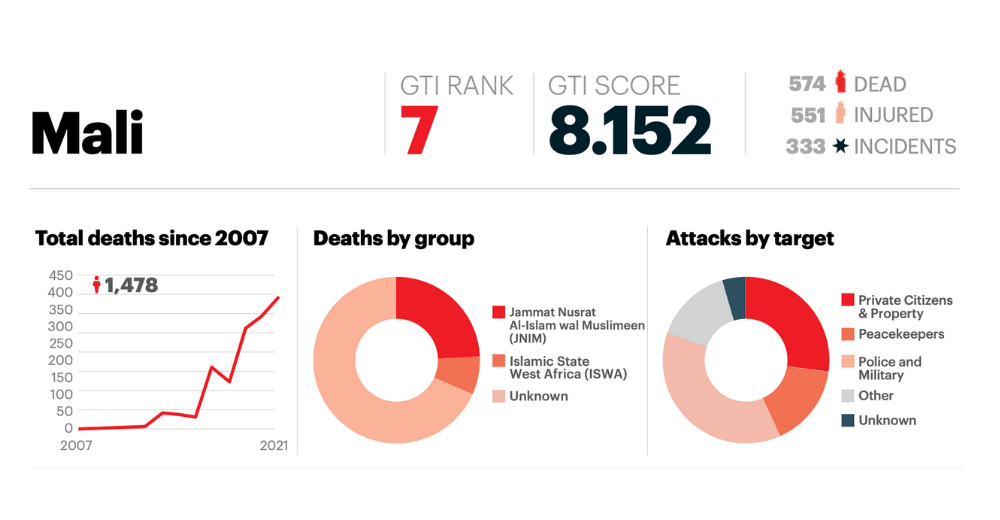

One of the worst attacks happened in Songho and Bandiagara where gunmen killed at least 33 civilians and injured at least seven others in an attack on a public bus on 3 December 2021. No group had claimed responsibility at the time of writing, but jihadists operate in the area.

One of the worst attacks happened in Songho and Bandiagara where gunmen killed at least 33 civilians and injured at least seven others in an attack on a public bus on 3 December 2021. No group had claimed responsibility at the time of writing, but jihadists operate in the area.