Chinese Naval Base in Guinea & Implications

Chinese Navy in Guinea, Africa

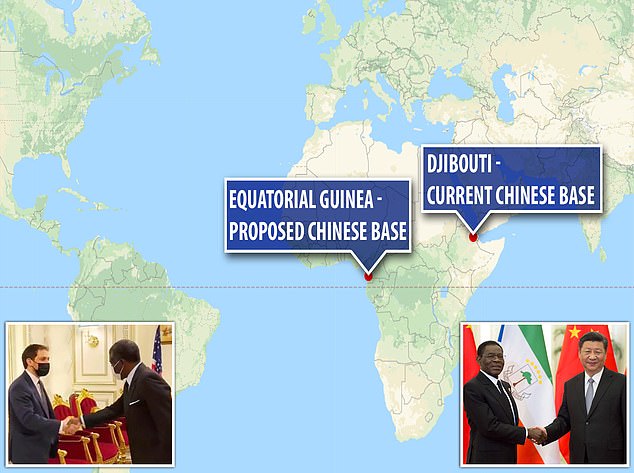

For several months now western media has been speculating that the Chinese Peoples’ Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is developing a position with the Government of Equatorial Guinea that will allow it to construct a naval base at the Equato-Guinean mainland port of Bata.

The flurry of interest in this plan was triggered by a publication in the Wall Street Journal on 05 December 2021 that reported upon an apparently “classified” piece of US intelligence that was the cause of “great concern” in Washington.

Indeed, this is no surprise as China wanting to establish a standing naval presence in the Atlantic Ocean, i.e. opposite the United States’ western seaboard, would naturally set alarm bells ringing.

So what would be the likely impact of such a development? In this analysis Arete examines:

- China’s strategic aims;

- The potential impact of the base on US and western naval strategy in the region;

- The potential impact on ongoing maritime security issues in the Gulf of Guinea.

China’s Strategic Aims

US defence officials believe the Chinese want a base on the Atlantic coast where they can replenish naval combat units with fuel, ammunition and consumables as well as create a facility where they can repair warships.

Gen. Stephen Townsend, Commander of U.S. Africa Command, said in May 2021 that “The Atlantic coast concerns me greatly”. His concerns are based on the short distance between the Atlantic’s eastern seaboard and that of the US and are most likely focused on the significant shortening of response times that the US currently enjoys and the potential for Chinese naval units to interdict western trade in the event of the current trade rivalry developing into a cold war scenario (or worse).

It is worth noting that China has a relationship with Equatorial Guinea that stretches back 50 years and its engineers have already made significant improvements to the port facilities at Bata – the largest city in the country.

China also has a large diplomatic mission in the country and has made significant investments in the country’s infrastructure, including roads and hydro-electric power facilities. Bata port currently has surplus capacity and has a dedicated basin for the Equato-Guinean Navy.

Nevertheless, if China were to utilise the facilities to any significant extent, the presence of multiple naval vessels would likely impact commercial operations. Therefore, it is probable that China will extend and improve the existing naval facilities or even build brand new facilities adjacent to the existing port.

Between 2014 and 2019, China was involved in 39 military exchanges with Gulf of Guinea partners, including the deployment of Chinese naval vessels which have conducted counter-piracy operations. Of this presence, only two exchanges took place with the Equatorial Guinean armed forces.

Figure 1. Gulf of Guinea showing location of port of Bata.

Figure 2. Port of Bata, Equatorial Guinea.

The construction of a naval base and the establishment of a permanent Chinese military presence in the region would reflect China’s strategic intent of ‘encircling’ the US in order to allow it to compete globally with US commercial interests.

In 2017, Beijing first established a presence on the continent when it set up shop in Djibouti, taking over former French facilities and justifying its presence by mounting counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea.

It is no coincidence that China selected Djibouti to establish its first major overseas military base, with Djibouti sitting on one of the world’s most important chokepoints for maritime trade. China spent $590 million dollars on the project, and it now has a toehold on the continent alongside the United States, Germany, Spain, Italy, France, the UK, Japan, and Saudi Arabia.

As strategically vital as Djibouti is, the US appears even more concerned about the potential for a Chinese military base on Africa’s western coastline. Dr. Freedom Onuoha, a senior lecturer at the Department of Political Science at the University of Nigeria–Nsukka, told Nigerian media that “A Chinese base in the Atlantic Ocean can play a decisive role in cutting off US access to strategic resources from many African states if conflict breaks out in the future. In a situation of intense hostility or great power confrontation in the future, it makes it a lot easier for China’s naval forces to stroll up and down Africa’s Atlantic coastline”.

Bata’s location is advantageous, sitting at the central point of the Gulf of Guinea coastline and enjoying the presence of the Equatorial Guinean island of Bioko off the coast – which would likely serve as a forward basing opportunity for defensive assets in the event of an international crisis between the US and China.

Aside from the strategic military advantage such a base would impart, China’s growing commercial interests and influence in the country worries US trade officials. American companies have invested heavily in the oil and gas sector in the country, with us oil majors and US service companies being pre-eminent to date in developing the country’s oil and gas resources. The presence of a Chinese military base would significantly elevate its leverage and influence in any future bidding rounds for future oil mining licenses in the country.

Furthermore, Washington has recently criticised the government of President Nguema for its poor adherence to international human rights standards and high levels of corruption. Such criticism will likely push Equatorial Guinea into the arms of a more ‘forgiving’ partner.

The power play between Washington and Beijing offers the chance for President Nguema’s government to leverage huge economic advantage for his country. However, playing two global powers off against one another is not without its own perils.

At this early stage, it is unclear whether the principal driver behind China’s regional ambitions are economic or the furtherance of their bid to become the pre-eminent global superpower. Europe has rested on its historical ties and been less proactive in maintaining and indeed developing them. This has been compounded by its reticence in doing business with countries that score low on governance.

China, however, has no such reservations. Indeed, Chinese companies have far lower interest in local content regulations and are disinclined to employ local people in senior and middle management positions.

With regards to other nation’s interests the UK’s new global position, following Brexit, has reinvigorated its interest in its Commonwealth partners and the EU also recently decided to compete with China’s Belt and Road initiative.

Thus, the stage is set for a contest between competing nations and trade bodies that may very well see African nations falling into debt traps, while western nations lose market share and influence in international bodies as African nations align more frequently with China.

The potential impact of the base on US and western naval strategy in the region

As the West realigns its energy requirements away from a Russia focussed supply market, the littoral states of West Africa, which all have oil and gas reserves to varying extents, have become more strategically important to Washington, Brussels and London.

This renders the Gulf of Guinea countries and their maritime trade routes and hubs of increasing strategic importance as highlighted in our previous #AreteDeepDive.

The presence of a Chinese permanent naval base in the region will almost certainly re-focus the minds of key decision makers in Washington and the US Africa Command (Africom) on how to counter the influence of the Chinese presence, and potentially how to neutralise its ability to interfere with trade routes deemed vital to western economic and security interests.

It is likely that the West will seek to establish basing rights of their own in the region, seeking to identify a country that is open to the attractiveness of huge investment in return for allowing a western military base on their territory.

Likely locations would be existing port facilities that could be expanded or developed, new space created for a western airbase and an agreement to allow the basing of manpower and the pre-positioning of logistics materials.

Recent events however will have worked to Beijing’s advantage. China will have watched the West’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine carefully including evaluating the thresholds of how far the West can be pushed and what tools and strategies it is prepared to deploy to contain an adversary.

The West, on the other hand, will have learned valuable lessons about how far and in which directions it can flex its muscles. One irrevocable effect of the war in Ukraine is that the West is now alert to its strategic weaknesses and is beginning to re-arm and remobilise its military potential.

At the moment, the focus is very much on containing Putin’s ambitions, however significant sections of the intelligence architecture and foreign policy departments of numerous western governments will have remained engaged in watching and assessing everything that China does. It is likely that key military powers in the West, notably the USA, United Kingdom and France will seek to match any expansion of Chinese influence in the region.

In the absence of permanent bases, it is likely that the US, UK and EU states will seek to have naval units almost on permanent station in the Gulf of Guinea should China’s plan come to fruition. In short it would be highly unlikely that they would allow the Chinese to dominate those waters uncontested. It might be that the UK and France look to their former colonies for support to deployed warships and the US to seek a permanent base for an Africom deployment.

The potential impact on maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea

Any foreign naval presence in the Gulf of Guinea will impose constraints on the ability of pirate action groups (PAG) to operate freely in the region’s waters noting that piracy incident rates have already seen a reduction in the last 15 months (most likely due to COVID and the effect on the world economy).

Indeed, Western naval deployments have already demonstrated the potential for impacting piracy as witnessed by the Danish frigate HMDS Esbern Snare against a PAG on 24 November 2021 and more recently, on 03 April 2022, we saw an Italian frigate, the Luigi Rizzo, respond to a call by a ship under attack 261 nautical miles southeast of Accra in Ghana. In both instances, the presence of the foreign vessel appears to have prevented pirates from carrying out a successful attack.

It is possible that the action by the Esbern Snare last November had a direct impact on driving down the rate of reported piracy incidents in the region, which are currently at their lowest rate for more than a decade. The action by the Italian vessel will also have likely reinforced doubt in the minds of the pirate group leaders as to the viability of their operations in a significantly more hostile environment.

If the Chinese were to join the fight against Gulf of Guinea piracy from a permanent base in the region, it would likely also have a significant effect on pirate actions in the region. China would almost certainly offer to provide an aggressive counter-piracy capability in the region as part of a hearts and minds campaign to portray their presence as being benign/benevolent.

Of course, such action would support China’s economic interests in the region and assist in securing its own strategic interests and trade routes.

In response it is likely the West would want to match any Chinese capability and presence in the region with the net effect being a (hopefully) more secure Gulf of Guinea for commercial shipping, which can only be regarded as a good outcome.

With all the above being said pirates in the Gulf of Guinea have proven themselves to be extremely resilient over many decades and maybe an international naval presence in international waters will simply push the PAGs to return to operating closer inshore in sovereign waters, e.g. the rivers and tributaries of the Niger Delta.