Red Sea Crisis

Background

During the night of 22-23 January, 2024, the UK and US launched another round of air strikes against Houthi targets in Yemen. Eight positions were struck in this series of strikes in a campaign of targeted attacks on Houthi positions identified as being linked to attacks on international shipping in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. The action is the latest move in the international geopolitical chess match that threatens to escalate the conflict locally and potentially expand it regionally.

The impact on shipping in the region and the knock-on effects on the global economy are significant. This analysis will examine the drivers behind the current crisis, the physical and commercial impact on shipping, the displacement of risk faced by vessels and mariners forced to use other routes to global markets and will offer a view on which countries are the winners and losers as a result of the Houthi campaign.

An armed Yemeni supporter of the Houthi movement sits on the back of an armored vehicle during an anti-Israel and anti-US rally in the Houthi-controlled capital Sanaa on January 22, 2024. (MOHAMMED HUWAIS / AFP)

For several months, shipping has been attacked by Houthi Rebels in the seas off the coast of Yemen. Houthi rebel forces in Yemen began their campaign against shipping in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden allegedly in response to the massive Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) response to the Hamas terrorist attacks against Israel on 07 October 2023. Their operational footprint encompasses one of the most important strategic choke points for international shipping and global trade, the Bab al Mandab Straits, which connects Asia to European markets.

This ‘accident of geography’ gives the Houthis a strategic advantage and elevates the impact they can inflict on global economic stability by an order of magnitude that, arguably, is disproportionate to their actual numbers and capabilities. Setting geography aside, like Hamas in Gaza, they also enjoy the patronage of Iran and benefit both logistically and in terms of training and financial support from their strong ties to Tehran and, in particular, the Iranian Republican Guard Corps (IRGC). Among other weaponry and equipment, the missiles and drones – and the necessary training – used by them to attack shipping are supplied by Tehran.

The waters of the region are a target rich environment for the Houthis, with as many as 400 ships in the area at any one time and a total of approximately 19,000 vessels transiting the Suez Canal every year. This number is now significantly diminished as shipping companies take the decision to sail the much longer and more costly route round the southern tip of Africa as they transit in both directions between the South Atlantic Ocean and the Indian Ocean.

The Houthis claim their campaign is aimed at bringing an end to the IDF campaign in Gaza. To that end, they claim their attacks have singled out vessels that have links to Israel, Israeli businesses or which are transiting to/from Israeli ports. As the attacks continue, this claim has been demonstrably weak, or even completely false, as Houthi attacks have struck vessels that do not fit these criteria.

Furthermore, Houthi rebels have been targeting shipping in the region since October 2015. By August 2019, a total of 40 attacks against shipping were attributed exclusively to Houthi rebels. These early attacks began with relatively unsophisticated attacks using hand-held weapons such as RPGs (rocket propelled grenades). This extremely common weapon system is not capable of sinking a vessel through breaching a hull, but if it were to strike a critical component of a vessel carrying a volatile cargo, such as an LNG carrier, the results could be severe. The attacks soon escalated, and by 2019, 22 incidents saw the use of the Chinese C-802 anti-ship cruise missiles (or its Iranian built clone, the Noor missile). In 9 instances, remote-controlled boats were utilized. The first of these attacks in January 2017, saw a drone boat attack on a Saudi warship off Hodeidah, resulting in the deaths of two Saudi sailors. These attacks were primarily against vessels involved in supporting the coalition that was attacking Houthi rebels in Yemen.

A US Navy ship launches missiles in the Red Sea, Feb. 3, 2024

The attacks since October 2023 took on a different characteristic. Following their threat against all shipping associated with Israel, and the firing of more than 100 missiles and drones in at least a dozen attacks in the weeks up to 21 December 2023, the 21 November 2023 heliborne assault and hijack of an Israeli-linked vessel, the MV Galaxy Leader, demonstrated to the world that the Houthis had evolved – or that they had direct support from the IRGC.

Following several warnings issued by the US through media statements, diplomatic channels and through international organisations, US patience finally ran out after a 03 January “Final Warning” was ignored and both the UK naval vessel HMS Diamond and several US Navy vessels were targeted on 09 January. The response was quick and substantial.

On 12 January, in the opening round of the operation (named Operation Prosperity Guardian), US and UK military forces attacked more than 60 targets in 28 locations in Yemen that had been identified as linked to the Houthi attacks on shipping off the coast of Yemen. 6 further strike packages were launched in the following 10 days, culminating in the 22-23 January strikes. The most recent strikes took place on 03 February and further strikes are expected, until such time as the Houthi missile and drone strikes against shipping cease.

The Houthis denied that the strikes had impacted their ability to launch attacks on shipping off the Yemen coast and stated that all US and UK vessels were now also targets. In an apparent demonstration of capability and intent, on 15 January, the US owned dry bulk cargo ship MV Gibraltar Eagle suffered a direct hit from a ballistic missile.

On 17 January, Houthis attacked the Marshall Islands-flagged, US owned and operated bulker MV Genco Picardy successfully hitting the superstructure of the vessel with a drone. No casualties were reported, but the attack was a clear demonstration that the Houthis were not intimidated by the air and cruise missile strikes of previous days.

The 22 January strikes were carried out primarily by UK and US assets, which launched weapons from aerial and both surface and submarine naval platforms. Additionally, Australia, Bahrain, Canada and the Netherlands contributed to the mission, supplying intelligence and surveillance in support of the targeting. Targets struck on this occasion included an underground storage site and other locations associated with missile and air surveillance capabilities. These strikes follow a series of 7 attacks which have involved a total of 10 countries. However, only the US and UK have been directly involved in launching weapons against targets on the ground.

Two ships with ties to the UK and US were also targeted in early February. MV Morning Tide, a UK-managed and owned vessel transited the Suez Canal on 02 February 2024, and was attacked approximately 57 miles west of Hodeidah, Yemen. Houthis fired three ballistic missiles at the vessel, all of them narrowly missing their target.

The second vessel targeted by the Houthis was the Greek-owned, Marshall Islands flagged bulk cargo carrier, MV Star Nasia. The ship is managed by a US-listed company called Star Bulk Carriers. The vessel also transited the Suez Canal at the end of January. The vessel reported an explosion approximately 50 metres from the ship soon after it had transited the Bab el-Mandeb straits. US Central Command (CENTCOM), stated that the vessel was attacked by three Houthi ballistic missiles over a period of 12 hours. The first missile reportedly missed the ship, although the ship was still caught in the blast radius and suffered minor damage. The second missile had no effect, and the third missile was shot down by the destroyer USS Laboon.

Houthi Spokesperson Yahya Saree, in a statement issued on 06 February claimed the attacks on the two vessels and stated strikes will continue to target all “Hostile American and British targets” along with Israeli shipping until the war in the Gaza Strip stops”.

Impact on Shipping

In November 2023, Houthis hijacked the car carrier MV Galaxy Leader. They brazenly released a video of the incident to the world exposing that they had been trained to a very high level – presumably by their Iranian patrons. Multiple attacks have seen the use of explosive weapons delivered either via missiles or drones. Their targets are diverse, including container ships, bulk carriers and, interestingly, a Russian oil tanker that was narrowly missed. A Houthi statement said the latter was targeted, allegedly, by mistake. This statement is possibly very significant, and we will revisit that later in the analysis.

On 16 January, Bloomberg reported that 114 vessels had passed through Bab el-Mandeb strait in the days immediately after the 12 January strikes. This was 17 transits fewer than in the previous week and a dramatic reduction on the 272 transits a month earlier.

By 22 January, a total of more than 30 attacks on shipping had been launched by Houthis according to a UK MOD statement. Other sources gave the number as 34 attacks. These attacks have impacted directly on a total of 55 countries according to flag state, ownership, cargo destination or crewing.

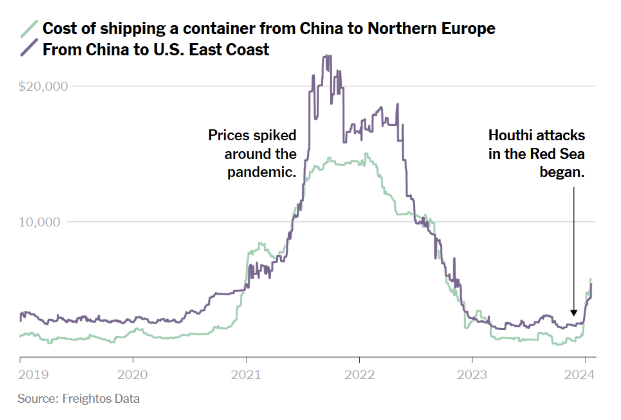

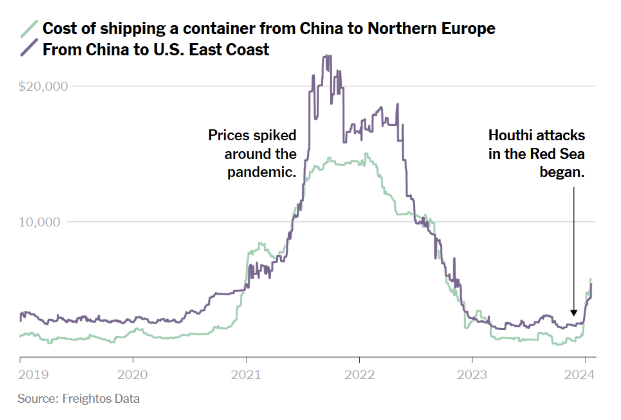

The diversion via the Cape of Good Hope adds approximately 6,000 miles to a journey from Asia to Europe. The effect of this is to push up prices in the markets as a result of increased fuel costs (Approximately $1 million) and operating costs (which include crewing costs, insurance costs, demurrage and more) and also to delay the arrival of goods to market by an average of 10 days in each direction. There is also a knock-on effect on port operations that also add costs to goods in the end markets.

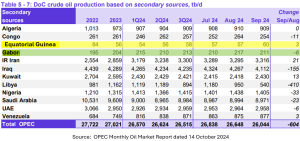

By 20 December, a total of 1.3 million 20-foot-long shipping containers had been diverted. Global oil benchmark prices rose by 1.2% in the same period. A further impact is the demand for shipping capacity is rising, driven by the increased duration of transits effectively ‘removing’ capacity from the shipping market. In turn, this pushes up chartering costs even further and the price consumers pay for goods at the final destination.

The model is not new. Shipping operators used this diversion route in March 2021 when the Suez Canal was blocked for six days when the container ship MV Ever Given ran aground, blocking the canal in both directions. Hundreds of ships were trapped in a holding pattern in the Red Sea for weeks, and the cost of shipping a container rose from $2,000 (€1,828) to $14,000. The Ever Given crisis added months of delays to goods imported from Asia. That crisis lasted for a week and the costs were profound. The current crisis has run for more than 3 months already and threatens to continue for an unknown duration. Car manufacturers in Europe have been forced to interrupt operations due to the delayed arrival of parts from Asia. The cost of shipping a container has tripled thus far and will likely increase further.

The impact of uncertainty on this scale will impact global markets, oil and gas spot prices, insurance premiums and drive inflation up, slowing economic recovery in countries in Europe. In mid-January, JPMorgan Chase estimated that worldwide consumer prices for goods would increase by an additional 0.7% in the first 6 months of 2024 unless the disruption to shipping ends. The name of the US operation – Prosperity Guardian – reflects the global strategic importance of the economics of this conflict. It is this economic impact that drove the European Union to finally agree to deploy military forces in support of the US/UK coalition operations in the region. Germany is deploying the Sachsen Class anti-aircraft frigate Hessen to the region. However, this vessel and any other EU assets will not be in position to operate until an unstated date in February.

New Risks?

With so many vessels diverting round the Cape of Good Hope, it is worth examining whether that diversion exposes shipping to other risks along that route.

Historically, piracy has been a serious problem in the waters off Somalia and as far south as the Mozambique channel. However, in 2022, according to International Maritime Bureau data, no acts of piracy were reported on the east coast of the continent. 2023 saw the return of piracy when a bulk carrier was hijacked off the coast of Oman and sailed towards Somalia. To date, 2024 has seen a single incident on 04 January when the 7 occupants of a skiff launched from a mother vessel, opened fire on a bulk carrier approximately 455nm SE of Eyl, Somalia. Although there has been a very small number of incidents in recent times, the return of deepwater attacks off the Horn of Africa indicate that a potential return of Somali based piracy is a real threat – although still a very limited one. Nevertheless, opportunistic criminal cartels might seek to take advantage of the increase in vessel transits in the region and could lead to a spike in piracy in coming weeks.

On the other side of the continent, the Gulf of Guinea became the world’s most active piracy hotspot in the years up to December 2021. However, since then, activity levels have been limited and certainly nothing like the levels seen in the years 2016-2021. Diverted vessels are unlikely to sail through the Gulf of Guinea directly, opting to take the shortest and fastest route between the Cape of Good Hope and the coast of Sierra Leone and Guinea. However, the last 2 years have each seen a vessel boarded and hijacked off Sierra Leone and a similar rate of activity off Abidjan in Cote d’Ivoire. To date, 2024 has seen just one piracy incident in West African waters when, on 01 January 2024, the Tuvalu flagged product tanker MT Hanna I was boarded 45 nautical miles south of Bioko Island, Equatorial Guinea and nine crewmen abducted. As with Somali groups, we have witnessed Nigerian based crime cartels operating in deep waters far from home so attacks can never be ruled out Historically, they have operated as far south as Angolan waters and as far west as Ivorian waters. Whilst the current threat is low, shipping companies should not ignore the latent threat posed by opportunistic criminals.

The above all being said, is assessed that the diversion of shipping round the southern cape will not substantially increase the risk to shipping posed by latent piracy groups either on the eastern coast or in the Gulf of Guinea given the current level of threat.

Who Benefits

A US Navy ship in the Red Sea [Aaron Lau/AFP]

Almost nobody is benefitting from the crisis in the Gulf of Aden and Red Sea. Interestingly and as mentioned above, the Houthis appear to have a benign attitude towards Russia and Russian linked shipping. This reflects the supportive stance that Russia has taken in denouncing the western naval presence in the region and the recent wave of US-led air strikes. The Houthis also have an unknown number of Soviet era legacy weapons that are now generally considered obsolete. It is not known if these are even still operational. Currently, Russia is not a direct supplier of weapons to the Houthis (and probably has none to spare given the intensity of the war it is prosecuting in Ukraine). The connection is probably somewhat more subtle and potentially even strategic.

Noting the Houthis are essentially an Iranian proxy force in the region (they are supplied and trained by Iran), it is also strongly suspected that Quds Force personnel are actually active in Yemen. Of course, Iran is a known ally of Russia and Putin, and it has been postulated by some analysts that the Hamas onslaught on 07 October 2023 against Israel, and the subsequent escalation of attacks on shipping in the Red Sea / Gulf of Aden, were both launched at the behest of the Iranian leadership in response to a Request from Moscow.

Ultimately Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine is not going according to plan so there is perhaps some credence to this theory noting that the actions of Hamas and the Houthis have drawn the attention of the US away from the conflict in Ukraine and focussed it on supporting its principal ally in the Levant. With a US presidential election in 9 months, Russia will be content to slowly erode US support for Ukraine in the hope that a Trump win will allow Russia to steamroller the dwindling Ukrainian forces in 2025 in the face of collapsing western support.

The above analysis is speculative, but it is credible, and the next 12 months will likely shape the future of Europe. The game and the stakes are enormous, and, unlike the US and its European allies, Russia is content to play a long game. In fact, Russia would prefer a protracted war in which it believes its vast resources will eventually ensure victory. So, a rapid suppression of the Houthis and the destruction of their ability to threaten shipping in the region is essential for a number of globally strategic reasons. Whether this can be achieved using only long-range attacks is a known-unknown.

The west is rightly nervous about any commitment of ground forces into the region as this would almost certainly result in a direct clash with Iranian forces, and that would escalate, expand and extend the conflict, none of which is desirable, particularly in a year when both the US and the UK have major elections.

Arete will continue to monitor and critically deconstruct events in the Middle East and shipping lanes around continental Africa.