Has Nigeria’s Piracy problem been solved?

Background

On 08 March 2022, the International Maritime Bureau (IMB) decided to remove Nigeria from its Piracy List in view of the dramatic reduction in the number of reported incidents of piracy in Nigerian waters. Following the report attributing the improvement in security to the efforts of the Nigerian Navy, the Chief of Naval Staff of the Nigerian Navy, Vice Admiral Awwal Zubairu Gambo, said:

“We will sustain the tempo of our Maritime Security Operations efforts. As you are all aware, the NN is the cardinal institution in the maritime sector that has the responsibility to lead the national response and prosecution of maritime threats. I make bold to say that the NN made giant strides in ensuring the security of the nation’s maritime environment. It is heart-warming to note the significant decline in piracy attacks by 77 percent on Nigerian waters as reflected in the International Maritime Bureau (IBM) Third Quarter 2021 report. I am glad to notify you that the latest IMB report (just last week) shows that Nigeria has exited the IMB Piracy List. However, considering the NN’s lead role in the regional effort at combating piracy and armed attack against shipping, the Service will not relent. Also, the NN’s effort at containing piracy in the nation’s maritime domain has earned us commendation by the Office of the National Security Adviser on behalf of the President Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, Federal Republic of Nigeria”.

The reduction in the number of incidents reported in the region has been significant, with no attacks recorded in Nigerian territorial waters or Exclusive Economic Zone since November 2021 and just four incidents being reported in the whole of the last 12-month period – one each in April, June, October, and November.

In light of the developments highlighted above, and given that Nigerian waters have not witnessed such low levels of piracy in any 12-month period since 2006, is there credible evidence to snow suggest that piracy in Nigeria is a thing of the past?

Introduction

The International Maritime Organisation defines an act in Article 101 of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) as consisting of any of the following acts:

(a) any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, committed for private ends by the crew or the passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft and directed:

(i) on the high seas, against another ship or aircraft, or against persons or property on board such ship or aircraft;

(ii) against a ship, aircraft, persons, or property in a place outside the jurisdiction of any State;

(b) any act of voluntary participation in the operation of a ship or of an aircraft with knowledge of facts making it a pirate ship or aircraft;

(c) any act of inciting or of intentionally facilitating an act described in subparagraph (a)

It defines armed robbery as:

(a) any illegal act of violence or detention or any act of depredation, or threat thereof, other than an act of piracy, committed for private ends and directed against a ship or against persons or property on board such a ship, within a State’s internal waters, archipelagic waters and territorial sea;

(b) any act of inciting or of intentionally facilitating an act described above.”

This analysis will consider all acts of maritime criminality that fit these definitions.

The analysis does not take into consideration criminal acts against vessels in ports, anchorages, and on the region navigable rivers unless they involve acts of extreme violence, kidnapping of mariners from internationally registered vessels, or hijacking of internationally registered vessels. The analysis will examine trends and patterns of activity going back to 01 January 2018 in order to provide some context to the reduction in activity witnessed in the last 12 months.

It is acknowledged that a great deal of maritime criminality occurred outside the parameters described above, but a full historical dissection of the region’s security history is beyond the scope of this article.

Historically, we have witnessed a number of evolutions in the maritime security threats that have plagued the Gulf of Guinea for almost two decades. To examine some of the more significant trends and patterns we will consider:

The annual ‘Ember Months’ spike:

Local wisdom warns us every year to be more security conscious in the Ember Months – November and December. Some people include ‘Octember’ in this warning. It is true that criminality increases in the run into the festive season as people resort to crime to ensure they can take care of their families over the holiday season. This phenomenon can be witnessed in the statistics for maritime and riverine criminality as well as onshore and urban crime patterns. Perhaps the starkest example of this phenomenon in the maritime environment occurred in 2020 when at least 15 acts of piracy occurred in Nigeria’s waters (and that excludes robbery in the ‘brown water’ environments). Previous years have seen an increase in the 4th quarter, but 2020 was demonstrative.

Mid-year lull:

In the years leading up to 2013, there was always a dramatic reduction in incidents in July and August. This was attributable to the fact that sea conditions were unfavourable for small craft operations and the pirate gangs at that stage had not yet moved into the use of motherships. From 2013, we saw a steady increase in the number of incidents in those months as the gangs used large vessels to reach further offshore and support small boat operations in deep water.

Election years:

Historically, as criminal gangs raise funds for their political patrons’ electoral campaigns, we have witnessed an increase in criminality both onshore and in Nigeria’s waters in the 12 months leading up to an election. These spikes might be very localised, such as off the coast of Bayelsa in 2010, and not particularly evident in the overall statistics for the period.

Changes – mother ships:

As mentioned above, the introduction of the use of motherships by pirate gangs allowed them to extend their reach, and from 2013 we started to see attacks occurring much further from the nearest landfall, and eventually the evolution of extended operational deployments into the waters of other Gulf of Guinea nations – with Nigerian gangs operating as far south as Angola and as far west as Liberia.

Migration to other waters:

The migration to the wider Gulf of Guinea environment also coincided with a more ‘industrial’ approach to kidnap for ransom activities, with pirate action groups (PAGs) deploying for several weeks and accumulating as many as 30 hostages. This behaviour had clear economic benefits for the PAGs, allowing them to collect much larger ransoms in both individual and cumulative terms, and in so doing, dramatically improving their profit margins. The gangs were clearly identified as Nigerian by the testimony of their victims upon release and also the fact that the kidnap victims were frequently held in camps in the Niger Delta.

Last six months – comparison

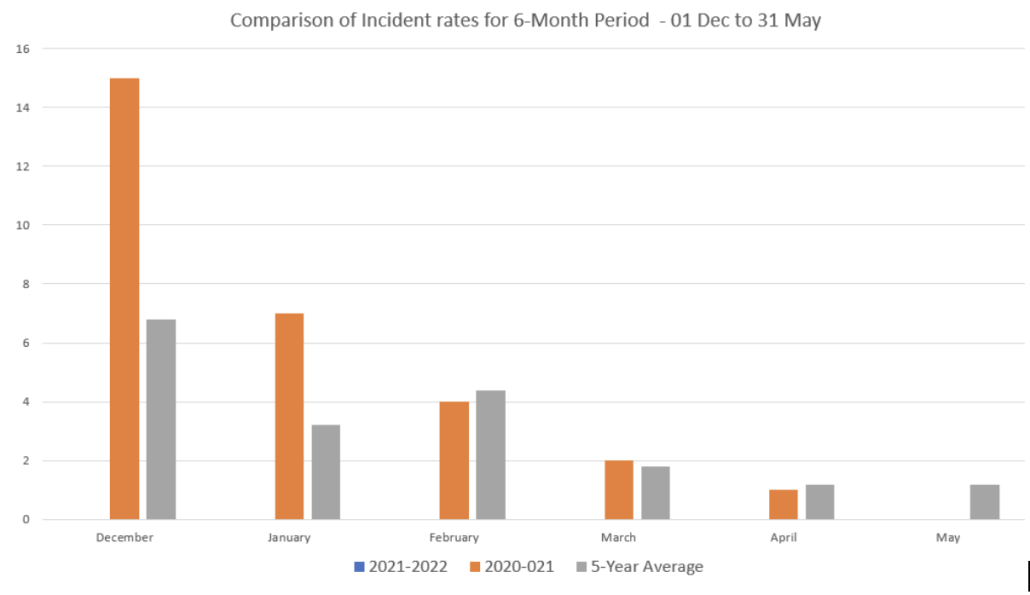

To illustrate the stark reduction in activity levels, we will compare activity in the last six calendar months (December 2021 through to May 2022) with the same period 12 months previously and also against the five-year rolling monthly average. The following graphs are based on data available to Arete.

This first graph shows very clearly the complete absence of activity in Nigerian waters in the last 6 months. The reality is that no acts of piracy were recorded in Nigerian waters in 8 of the last 12 months. There have only been three other months (August 2018, November 2019, and August 2020) in the period Jan 2018 to Dec 2020 in which there were no incidents recorded in Nigerian waters. However, in August 2018, an incident occurred in Gabonese waters that were attributed to Nigerian pirates, and in November 2019, five incidents occurred in the waters of Togo, Benin, Sao Tome & Principe, and Equatorial Guinea. In August 2020, a single incident occurred in Ghanaian waters.

An absence of reported incidents that matches the current hiatus in activity has not been witnessed for two decades or more. However, the keyword is hiatus. We do not know how long this period of grace will last as the organised crime groups (OCGs) that launch the PAGs likely still exist, still own their motherships and retain the capacity and capability to mount further operations at relatively short notice.

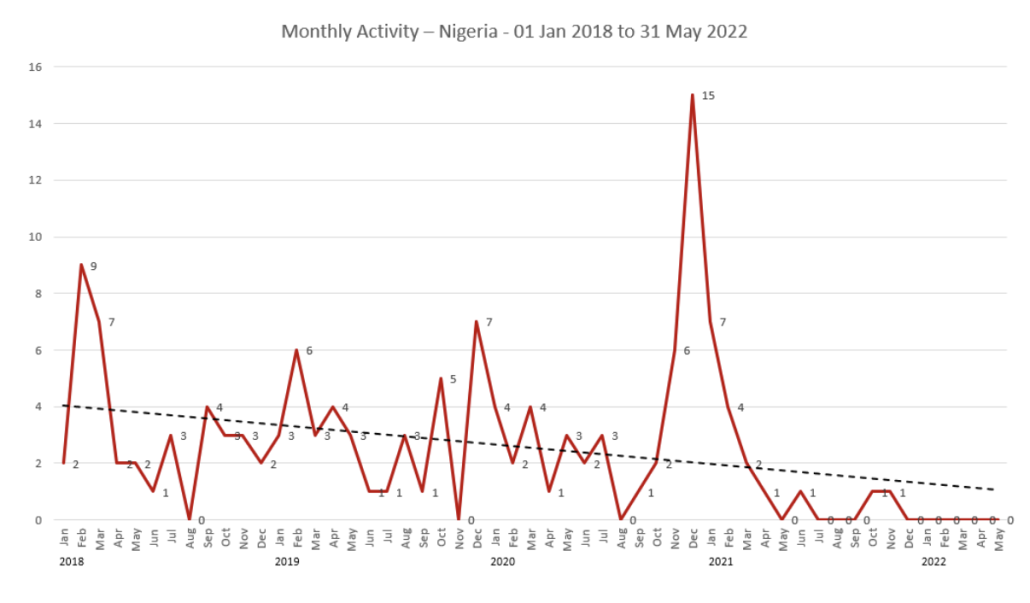

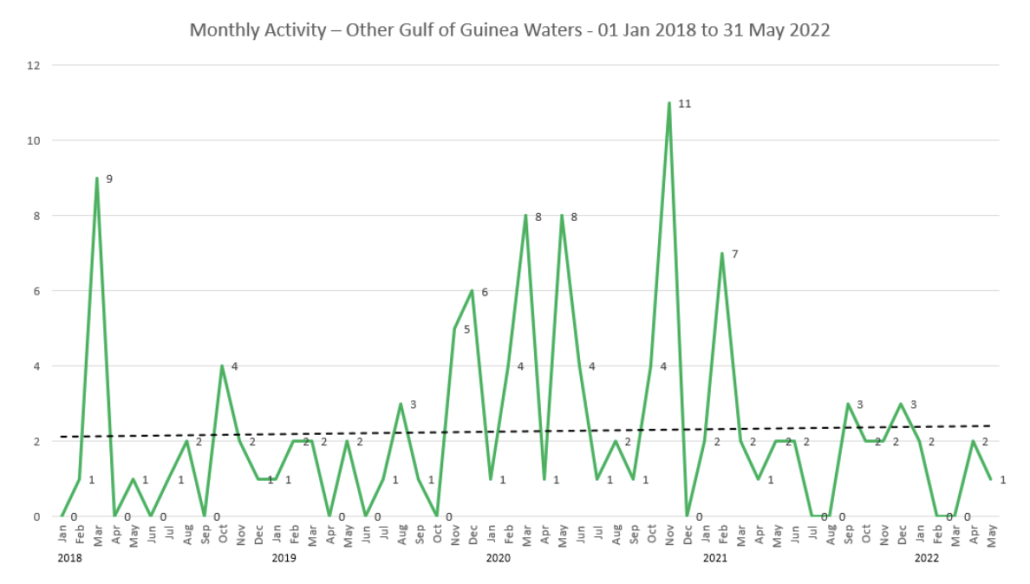

This second graph shows the monthly activity rates since 01 January 2018 for Nigerian territorial waters and EEZ. It is clear that despite the peaks and troughs in activity levels, the overall trend is downwards towards the current extremely low levels. However, if we look at the next graph, which includes similar incidents in the waters, with the exception of Nigeria’s, between Ivory Coast in the West and Congo Republic in the south, the picture is slightly different.

This graph shows a trend line with a very gentle upward gradient, which persists through the currently extremely low levels of activity in Nigerian waters. Nevertheless, the graph also shows a significant general reduction in incident rates in ‘foreign’ waters over the last 12 months when compared to the preceding 12-month period. This almost certainly reflects the fact that most of the piracy attacks in the whole of the Gulf of Guinea are carried out by Nigeria-based OCGs/PAGs.

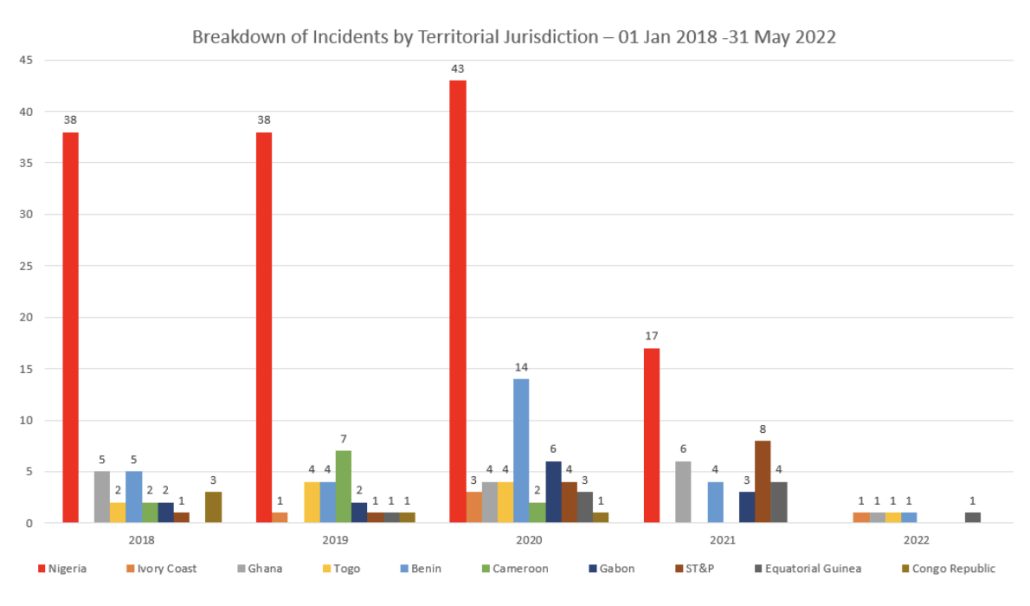

As a more direct comparison, the following graph shows annual totals for the various territorial waters and EEZs of the littoral states of the Gulf of Guinea.

What is interesting is that even after the marked reduction in Nigerian waters, activity persists in the jurisdictions of other Gulf of Guinea states. It also reflects the predominance of activity in the Nigerian EEZ, which is likely a reflection of the density of available targets, the ease of reach from the home bases of the PAGs, and the range of the mother ships being used, and the endurance of their crews.

It is thought that the PAGs operate in the waters of neighbouring nations in the view that the naval threat is lower in some of those states. Of interest is the spike of activity in the waters of the Congo Republic in 2021, which coincides with the reduction in activity in Nigerian waters.

So what?

All of the above point to a number of key questions:

How long will the hiatus last?

This depends entirely on what is driving the absence of PAG activity. If the OCG/PAGs have found another more lucrative or less risky revenue stream, then the hiatus is likely to last. Of course, if the OCGs have responded to external pressure from the Federal Government then again, it could last – at least until there is a change of government.

Have the OCGs shifted their operations to another source of income onshore?

It is possible. However, there has not been any noticeable spike in other criminality onshore or indeed the emergence of any new form of organised crime. Oil bunkering is at an all-time high, and it is possible that some of the OCGs are also involved in that activity and have shifted their efforts into that arena. It is possible, as the industrialised theft of oil and condensate no longer attracts the international condemnation and attention that the piracy was attracting.

Have the PAGs retained their capacity and capability to resume operations?

As far as we know, they have not burnt their boats on the beaches. That must mean they have either sold them or retained them. Some of the mothership’s identities were well known and it is likely that had they been sold as they would have required a complete change of identity in order to operate unmolested by indigenous and international security forces in the region. For now, we have no evidence to suggest that the capacity and capability of the PAGs have been removed from the OCGs.

Is this a reflection of a reporting anomaly?

This has been touched on above. Reporting of activity in Nigeria and West Africa has always been incomplete, sometimes misleading, and sometimes mischievously so. However, it is interesting that reporting of activity in anchorages and ports has also fallen away sharply. There are lots of political and commercial factors that could be behind that, including the cancellation of the Secure Anchorage Area contract in early 2020. We cannot rule out that the anchorages and ports are suddenly a lot safer. The data would suggest that is the case. Anecdotal information would suggest otherwise.

What could have forced the change?

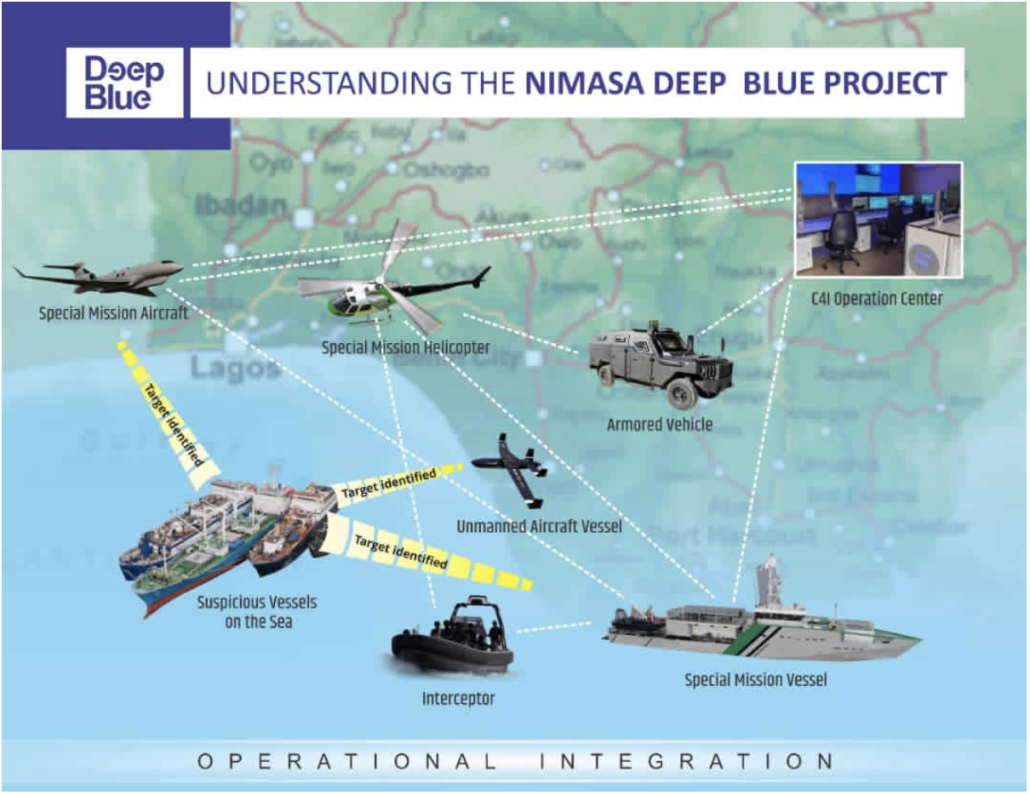

Deep Blue:

The much-vaunted Deep Blue project that married NIMASA operations with those of the Nigerian Navy has been claimed to have changed the security dynamics in quantum leaps. However, it has not been possible to find any substantive evidence that the Deep Blue project now dominates the maritime environment off the coast of Nigeria.

International patrols – Danish naval action:

The presence of international warships in the region was certainly a game-changer in 2021. Several interactions between western and Chinese warships and vessels under attack were reported. The intervention that perhaps had the greatest impact was that of the Danish frigate Esbern Snare, which intercepted a PAG while in the act of attacking a commercial vessel deep off the coast of Nigeria in November 2021. The incident resulted in four pirates being killed and five being taken into custody. There have been no incidents in Nigeria’s EEZ since that event.

International political and commercial pressure:

One very interesting possibility is the international pressure that could have been brought to bear through commercial (mainly insurance) channels and also closed diplomatic channels. The precedent for the latter form of intervention was apparently set when the enduring problem of extended hijacking for cargo theft was brought to an abrupt halt. The cartels involved in that form of criminality simply ceased operating. It cannot be ruled out that a similar intervention might have induced the pirate gangs to ‘seek other work’. The commercial impact that the Lloyds Joint War Risk Committee classification of Nigeria’s waters has had on the Nigerian economy has been significant. In November 2021, NIMASA stated that it was determined to have the War Risk Insurance Surcharges removed from vessels operating in Nigerian waters. It cannot be ruled out that the federal authorities identified the big men behind the OCGs responsible for the piracy and persuaded them to ‘seek other work’.

Have the big men behind the piracy made enough money to ‘retire’?

This is another possibility that cannot be ruled out entirely. The precedent was set when the kingpins behind the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) were effectively bought off by the 2009 Niger Delta Amnesty program payments, and the award to their newly formed companies of huge contracts – mostly to protect the assets they had previously been plundering. So major criminal actors do sometimes “read the tea leaves” and decide to retire while they are ahead. On the other hand, it is strongly suspected that the PAGs operating out of Nigeria belonged to five or six separate OCGs. It is unlikely that the bosses of all the groups decided to shut up shop at the same time.

So, the question “What induced the pirates to stop their operations?” remains unanswered with any certainty at this time.

What Next?

There remains a huge amount of uncertainty in the security environment in Nigeria. The forthcoming elections in early 2023 will likely shape the future security architecture in the country for the subsequent 8 years at least. It is known that the Presidency is greatly concerned about the currently held views of the electorate regarding security in the country. This was brought to a head by the attack on the Abuja-Kaduna train attack on 28 March 2022. A significant amount of energy and time has been spent discussing the various security challenges facing the country and the Presidency is determined to make a difference before the end of the year and the run-in to the polls.

It is likely the impact of piracy on the country’s economy has driven the launch of Deep Blue and the Navy’s focus on generating a safer and more secure environment for mariners. The country now rests on a political fulcrum and the security challenges have the potential to tip the elections against the ruling party. Therefore, it is likely that more resources will be introduced into the battle against the pirates being fought by the Nigerian security organisations in the coming months.

Nevertheless, Nigerian security forces have 39,700 sq. km to patrol and secure. That is a huge challenge, and the assets and resources are not yet in place to ensure security for mariners operating in the area.

Summary

Shipping companies and offshore operators should be prepared to meet the security challenges of short-notice or no-notice increases in the threats facing them in the Gulf of Guinea. The threat currently is assessed to be dormant and it could emerge again very quickly. Pirates live on the land and their families stay on the land (mostly). They are driven and controlled, by onshore factors – poverty, greed, politics, bribery, corruption, and even adventure. Nigeria is moving into an election process, and like any election in any country, it generates uncertainty and, for some people, fear for their future.

Shipping companies should avoid immediately seeking to cut costs. The situation remains uncertain, and the Joint War Risk Committee still classifies the waters of the region as a listed area – meaning they consider the risk to be high. For now, despite the economic pressures being at an all-time high, shipping companies should avoid being seduced by pronouncements that piracy is a thing of the past.